(Last updated March 6, 2016)

Lately, methane levels in the arctic have been spiking to unheard of high levels. What does this mean?

_______

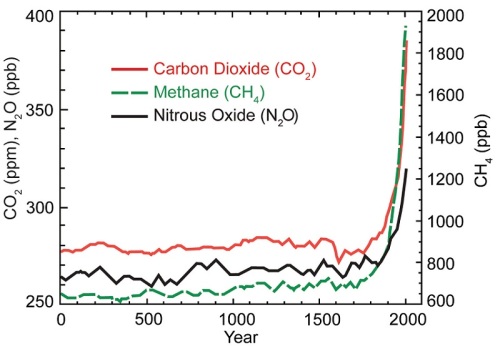

We can tell from extensive ice core sampling that for at least the last 800,000 years, average ambient methane – or CH4 – levels apparently never rose above around 800 ppb (parts per billion), in the earth’s global atmosphere.

Yet in the modern industrial age – a pinprick of geologic time – average levels of this potent greenhouse gas have suddenly risen by an amount that’s more than double the highest concentrations recorded in at least 800,000 – i.e, not far from a million – years, and possibly longer.

And in the Arctic, where concentrations of late have been particularly high, last fall and again this past spring, methane levels have at times spiked an additional 800 ppb or more above that.

Update: Lately methane has been spiking even higher still, and Winter 2016 saw the previous highs not just beaten, but shattered, as NOAA’s METOP orbiting polar satellites in late February recorded a spike to a whopping 3096 parts per billion:

_______

Through a multitude of processes – enteric fermentation in ruminants (cows, camels, goats), landfills, energy production, etc., methane levels – from a geological perspective – have skyrocketed.

Pay close attention to the left side of the EPA chart below, and note how from a geologic perspective methane levels (as with CO2), have shot straight up – suddenly going frrom around 700 -750 ppb, to over 1800.

Given methane’s fairly rapid rate of breakdown, it leveled off near 1800 ppb in the atmosphere in the very early 2000s. (To keep levels high, let alone continue to increase it, requires a lot of ongoing net emissions, since methane’s half life is only around 6 to 9 years.) But since 2007, levels have been slightly increasing, and are currently a little over 1800 ppb. (As of Winter 2016, average ambient atmospheric methane levels are around 1830 ppb – which given methane’s fairly rapid breakdown, means large – even increasing total amounts – are still being emitted. And in the arctic and surrounding northern polar latitudes, it appears the surface of the earth’s methane potential is just starting to be scratched – see below .)

Methane – It’s History, and What’s Happened Now

About 2000 years ago – or 1/400th of an 800,000 year period – levels of this potent greenhouse gas were a little bit above 600 ppb, and, in part through human activity ( rice cultivation -which is a form of wetlands, which are otherwise large natural emitters of methane -increasing domestication of ruminant animals, etc.) that rate “crept up” to around 700 ppb around the year 1600. (Which is also roughly around the height of Western European deforestation, when all but an estimated 5-15% of Western Europe forests had been cleared.)

Total atmospheric methane then tailed off slightly, then started to creep up a little faster to right around the start of the industrial revolution, where it was nearing 800, which is slightly above its highest point for more than the last three quarter million years. (Graph by EPA):

Then, particularly as we moved into the 20th century, from a geologic perspective levels of this gas essentially started to shoot straight up, comprising a rise from around 700 – 800 ppb around the years 1800 – 1850 – and just about the highest methane had also ever been over the past 800,000 years – to a concentration a little over 1800 ppb today. With again, similar to the rapid rise in CO2 over what is also a mere geologic moment – the far more significant part of that rise occurring over an even shorter time period. .

In other words, until recently, as far as we can tell from ice core sampling, the earth over the past 800,000 years had not seen an ambient atmospheric methane concentration level above the high 700s.

Yet today ambient global methane levels stand at a little over 1800 ppb. And in the arctic this past October, methane levels shot up to an amount more than 800 ppb over that, as atmospheric concentrations of methane over the arctic region reached 2666 ppb.

Again, this also occurred this past spring (when they actually went up to 2845, almost 200 ppb higher than in the fall), and, although a little lower, in early fall of 2013 a well, when methane levels spiked to over 2500 ppb in the arctic.

Why is Methane Seemingly Starting to Move Upward Again, Particularly in the Arctic Region

Additional arctic methane spiking happens when northern permafrost areas start to slowly melt. While seemingly minor right now, the issue isn’t so minor, as permafrost covers about 24% of the northern hemisphere’s total land mass, and it’s slowly starting to change. (In fact, in one of the many indices of “hidden” changes beyond what we simply feel when we open a window, in many shallow frozen and partially frozen northern permafrost areas, the actual ground just below the permafrost has warmed more, sometimes considerably more, than the ambient air just above the surface of the frozen area. Which is kind of remarkable when you think about it, and bodes a lot more long term change than mere, “ephemeral” and always changing air temperatures.)

And, more fitting for a movie than a science piece, it also happens when shallow sea bed areas – essentially frozen solid for hundreds of thousands of years if not more – warm up and thaw sufficiently to release methane that’s otherwise tightly bound up in copious amounts in frozen clathrates along much of the upper ocean shelf sea bed floor, leading to the eruption of methane gas.

When methane bubbles up, it’s sexier, or eerier, than the simple emission of carbon dioxide into the air: It erupts out of the sea bed bottom and, lacking buoyancy, if enough of it displaces water on its way up, can literally cause a ship to sink straight down in what would appear to the outside world as an unsolved mystery.

This is interesting in small amounts (though not for any ship that happens to be in the wrong place at the wrong time).

But it’s also something that in large amounts will have a fantastic impact upon our world, due to the powerful heat energy absorbing properties of methane in comparison with the far weaker carbon dioxide molecule and – along the massive amount of carbon “stored” in the northern land permafrost – the huge quantities of methane on our sea bed floors that after long epochs of geologic time, and not at all “coincidentally,” are now suddenly starting to thaw.

How is this thawing happening?

While there is great variability from year to year, each year, on average, less and less arctic sea ice – which in the past has dwindled during late summers somewhat but for the most part essentially remained year round – exists by late summer in the northern polar arctic region.

In fact, over the past several decades, summer arctic sea ice extent has been decreasing by a little over 13% per decade.

This change is critical. Darker ocean water absorbs a much broader spectrum of incoming solar radiation – for the same reason that when you wear a dark shirt in the sunlight, you are warmer than when you wear a white shirt.

Reflected solar radiation doesn’t have nearly the same effect as absorbed solar radiation.

Solar radiation is mainly short wave radiation, and atmospheric greenhouse gases predominantly absorb and re-rediate medium to long wave length radiation. But when solar radiation is instead absorbed, that heat energy isn’t reflected back into the atmosphere (where in turn it is largely unmolested by the greenhouse gas molecules that otherwise keep our planet warm), but is transferred into the absorbing body. Yours and your clothes if you are wearing dark clothes, for instance. Or a dark macadam surface. Etc.

Additionally, when some of that heat is given off by the absorbing body or earth surface or water surface area, it is emitted as thermal radiation, not solar radiation.

Although warm matter can also convey heat via conduction, the passing of heat via molecules to cooler, neighboring molecules – though here directly to molecules of gas, not solids as is the normal definition of conduction – as well as by convection, which is the passing of molecular heat from or to a gas or liquid, and, via conduction to gases such as air, which then frequently results in air currents that then transfer that that heat outward – as for example you may feel when sitting near a fireplace.

Thermal radiation, on the other hand, is in the medium to long wave radiation form: This is the radiation wavelength range absorbed and re radiated by greenhouse gases. While again, the short wave solar radiation that is incoming from the sun, and then to some extent reflected back out by various surfaces, is essentially not absorbed and re radiated.

The measure of a surface’s reflectivity is its albedo. The albedo of open ocean water is low, and in high latitudes it’s as as low as 10%: Meaning that almost all of the incoming solar radiation is absorbed.

Contrast that with a nice solid layer of light colored and highly reflective sea ice sitting atop the arctic waters instead – where most of the incoming solar radiation is reflected.

Snow and sea ice have a very high albedo. This is in part why large northern, southern, and until recently mainly high mountainous but much smaller ice sheets, tend to perpetuate local climate conditions, and remain relatively stable.

Although even that is now changing with respect to the very large thick ice sheets that sit atop the land at both our northern and southern polar regions: Mainly Greenland in the north (the actual area surrounding the north pole itself is all ocean water), and Antarctica – a continent that actually sits atop the pole – in the south.

Both regions are experiencing a net loss of total glacial ice; and, far more tellingly, both are experiencing it an accelerating rate, with even East Antarctica – which until very recently was thought to be extremely stable – despite ongoing atmosphere and ocean changes – getting in on the act.

This increasing rate of acceleration is not just relevant in the Antarctic, where as noted above a part of the ice sheet is now considered on a pathway of unstoppable loss, but particularly in the smaller – and thus less stable – and not quite as “polar” Greenland area. (The north pole region is open water, which used to be mainly frozen year round, but while there is wild variation from year to year, long term that is changing, and also at a fairly rapid geological clip, and leaving more and move summer water open to absorb instead of reflect the summertime solar radiation, while the south pole region is covered by the frozen but now starting to in part thaw continent of Antarctica.)

Greenland likely melted less than a million years ago, and, with far more changes in energy input into our system than occurred less than a million years ago, is increasingly likely to again.

This is an area that contains enough ice to raise the world ocean not by the few feet that the IPCC – tending to leave out many considerations on which there is still a wide range of uncertainty – usually tosses out; but by over 20 feet. Greenland, like West Antarctica, is also starting to see ice sheet melt at an accelerating rate: So much so that rivers are now forming along its surface to speed away melting snow and ice, while also hastening and accelerating the melting process, since water itself – and moving water even more so – is a melting accelerant.

And while we conjecture, we really don’t know just how fast melt acceleration can or will occur with a globe that is accumulating net long term heat energy – and one that for very specific and still even rapidly increasing reasons – doing so at a geologically breakneck, and increasing, pace.

For instance, as the World Meteorological Organization pointed out in its last Statement on the Status of the Global Climate (emphasis added):

93 per cent of the excess heat trapped in the Earth system between 1971 and 2010 was taken up by the ocean. From around 1980 to 2000, the ocean gained about 50 zettajoules [10 to the 21st power] of heat. Between 2000 and 2013, it added about three times that amount.

In other words, in the thirteen years between 2000 and 2013, our ocean gained more than 3 times the energy that it did in the 20 years from 1980 to 2000.

There’s presently a sort of fiction in even some climate change concerned circles that this is “absorbed heat” that mitigates the effect of “climate change.” We’ll get into that in another post (as well as below when looking at methane clathrate eruptions):

But essentially the heat retained by the ocean is simply a reflection of excess atmospheric heat energy over the earth’s surface (mainly ocean, as water can absorb a great deal of heat, and do so more easily than land surfaces, which stay fairly insulated very close to the surface). This in turn becomes part of our climate system over time, and reflects a key part of what drives and directly affects what drives our climate.

For instance, extra heat is not “hidden” in oceans, it affects those oceans and how the oceans ultimately affect the world, through a multitude of processes.One of which is warming sea columns in shallower ocean areas, warming up long frozen sea bed floors containing large amount of previously well contained or “trapped” methane.

The insulating Process

The earth’s climate is driven by the stabilizing and moderating forces of it’s geo-physiology – its oceans ice caps and, secondarily, attendant global patterns of tendencies. (Such as ocean currents, etc. Also note that not only do the polar ice caps play a key role in moderating and generally stabilizing earth’s temperatures, but even relatively minor changes in them can have a very large impact upon climatic conditions.)

And it’s driven more directly and immediately, of course, by the source of almost all energy: The sun, and then the amount of solar radiation, transformed after absorption into thermal radiation upon release from any surface area of a warmed body, that is then re-absorbed and re-radiated by the total greenhouse gases in our lower atmosphere, at which is incoming, both originally, and then again prevented from rom esIncoming energy, in the meantime, is a combination of the sun, which of course is what it is; and less directly, the level of atmospheric greenhouse gases, which absorb and re radiate heat.

These infamous greenhouse gases (though the term is sometimes sloppily used synonymously with carbon dioxide) are already at massively high levels for our current epoch – already higher in the case of CO2 alone than in the past few million years. (That measurement also doesn’t even take into account large increases in methane, nitrous oxides, and fluorocarbons which when added in terms of each’s “global warming potential equivalent” or thermal radiation absorption and re-radiation properties relative to a unit of carbon dioxide, add considerably more to the total long term molecular atmospheric increase in re captured energy.)

And, through activities that we could curtail, alter, or transform (mainly multiple traditional agricultural and energy practices), these levels are still skyrocketing. That is, from a geologic perspective, as noted at the outset, they are essentially shooting straight up.

These greenhouses gases also include water vapor, the most important greenhouse gas at any one time, and one which we’re not affecting directly. But water vapor is not long lived, but ephemeral. Thus it’s not a driver of long term climate, but a response to it, and a part of weather itself. With a warming world, the atmosphere will likely lead to the evaporation of, and retain, more moisture.

Since it can hold more moisture, this might mean increased precipitation intensities and changing patterns, one of the most likely long term responses to our ongoing change – although exactly how precipitation patterns will change is unclear. (What is clear is that our current fauna and flora as well as river systems, and current anthropogenic agricultural areas and systems, evolved under the general global and regional patterns of the past few million and in particular past few hundred thousand years.)

If it means more precipitation overall, much of this could come in less frequent but much more intense precipitation events. Though more precipitation overall would be far more welcome than less overall in an otherwise still warming world, it would also likely mean an amplification of the ongoing “greenhouse” affect, since it would mean an increase in average total atmospheric water vapor levels.

While water vapor acts as an atmospheric reflective agent during the day – increasing earth’s overall albedo by reflecting a lot of sunlight right back up before it even penetrates through the atmosphere down to the ground, it also acts as a powerful greenhouse gas simply due to the massive concentrations relative to the other greenhouse gases, “trapping” in thermally radiated heat.

Both of these phenomenon – increased heat retention through energy re absorption and re-radiation (“re-capture”) , as well as increased solar radiation reflectivity – are at play during the day. At night, only the powerful greenhouse effect of increased water vapor is at play, leading to an overall further amplifying effect if water vapor levels are generally increased.

On the other hand – although so far the evidence doesn’t seem to support this being the case, but almost anything could change in terms of precipitation patterns as we move forward – if water vapor decreases despite a higher overall rate of evaporation due to warmer temperatures, this would heavily exacerbate what is likely to be one of the most fundamental problems caused by our change set of climatic conditions as it is: Drought.

Remember, even with increased precipitation, with more water vapor being held in the atmosphere, as well as shifting regional patterns, regions used to receiving rainfall could easily experience huge shifts and become regions that receive almost no rainfall at all (and vice versa) whereas many areas could receive the same or even more rainfall, but with precipitation events both far more intense, yet less frequent, etc, with thus far more of that precipitation lost to runoff under our current evolved world, including its rivers, topsoils, and root structures – as well as intensified flooding.

Drought and changing precipitation patterns, particularly for the poorer areas of the globe, is likely to be one of the most directly devastating affects of ongoing climate “change,” and while a lessening of some of the greenhouse effect from reduced water vapor would be welcome in that sense, a decrease in overall precipitation along with changed patterns, likely increases precipitation fall intensities, and overall warming would be a particularly negative, possibly – at least in terms of what we are used to (and have come to rely upon) right now – mind blowingly devastating development.

So while water vapor is a bit of wild card, it’s not really a good wild card in either direction. And there is a fundamental reason for this. We evolved, and the species we relied upon evolved, under the conditions of the past few million years. And those conditions are changing.

A Look At the Bigger Picture

While both polar glacial ice regions are decreasing in total ice mass, and far more notably, at an accelerating rate, the smaller, “less” stable Greenland ice sheets in particular are starting to show increasing signs of marked change. And in just the last five years – a remarkably short period of time – the extent of net melt loss from both polar regions together has doubled. In the apt words of Angelika Humbert from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute, this is an “incredible” amount.

(Do a little math. While there is no reason to expect this (or, for that matter, not expect it), if that pattern were to continue – i.e. regardless of size just keep doubling the loss every five years – it wouldn’t be long before a good portion of Florida, and many other areas, would be completely underwater. In the U.S. for example, you might want to start investing in Arizona “beachfront” property, now.)

Greenland is also more conducive to easy climatic change than the vastly larger and colder antarctic region, as again even some 400,000 to 800,00 years ago, for a time it was not a large sheet of ice, but instead covered by fauna and flora; and the world’s oceans, correspondingly, were much higher.

Whatever happened less than a million years ago, also keep in mind that the level of energy alteration we are currently undergoing is already on a multi million year level scale, and it is also one that, simultaneously, is still increasing. Fast. And from a geologic perspective, extraordinarily fast.

This rate of change is something we tend to confuse with our own sense of time; thinking that effects upon this enormous, structured system would be near instantaneous, when they will shift and accelerate, even lurch, over longer and largely unpredictable periods of time, as the net energy balance of the earth lower atmosphere continues to grow, and as these underlying and normally stable structural ecological systems – such as our ocean, ice sheets, and others – start to change over time at an accelerating rate.

And they will do so in most cases, with some sort of positive feedback. Such as, for instance, in the case of warming shallow ocean region water columns, which are showing very early signs, again, of releasing long frozen solid methane clathrate deposits up into the surrounding ocean waters, where they bubble up, and release out into the air. Where, in turn, they add to the process of increasing net energy retention (prompting yet more melting, etc), even further.

(You might think it’s “odd” that things happen to be reinforcing, but this is because the two most critical elements in all of this often get completely overlooked. 1) This entire phenomenon represents what is in effect an external, or “forced” change in energy input – from something outside the natural system – namely, in this case our alteration of it. 2) It is geologically massive.)

In the arctic region where these methane spikes are seemingly becoming more prominent, the summer sea ice extent continues to decline, and there is a massive change in the surface albedo of these summer waters – that is, as the surface changes from the high reflectivity of an extensive ice coverage area, to the extremely low reflectivity of dark colored, high latitude open ocean.

And remember, this matters, since the ice depletion, of course, is occurring in summer when the north pole is angled toward the sun and receives its rays.

While at the same time, the 1% a year or so increase in southern polar sea ice extent, that is probably due largely to an increase in the Southern Annular Mode wind patterns pushing more of the ice northward and making room for growth, as well as concomitant near freezing upper surface water insulation from melting glacial run off is during the southern hemisphere winter months.

So with increasingly less arctic sea ice, the arctic ocean sometimes gets a lot warmer. And this in turn leads to some interesting things that sound like they are on the cutting edge of science fiction, but that are very real.

Namely, this eruption, or thawing, of methane clathrates that exist in large quantities amounts on sea bed floor areas, and that contain a massive amount of this long “contained” methane gas. (It is not that clathrates never released before. It is that the process has likely moved from a relative rarity in terms of occurrence and amount – and thus insignificant – to one that is increasingly significant, just as would be expected if shallow ocean bed areas – which generally tend to be very stable in temperature but are not that far below freezing temperature – were to warm.)

Current estimates of the amount of methane so “trapped,” most of it in shallower areas more susceptible to thawing, have come down; as it has been discovered that the far deeper ocean floor areas contain very little of it. (These far deeper areas are also far less susceptible to thawing anyway, and in fact some studies have suggested that some of the deeper ocean waters have not warmed at all, while other deep ocean parts have, but these areas are hard to gauge, since they’re not easily accessible.)

Yet the estimates still average out to more than the total amount of carbon (about 750-800 gigatonnes, or a little under 3000 gigatonnes of actual carbon dioxide) in our global entire atmosphere.

That’s a lot. But even more relevantly, methane gas is a much more potent absorbent of thermal radiation than carbon dioxide. This causes a lot of confusion and assumptions, since methane breaks down into carbon dioxide, with a half life typically of somewhere around 7 or 8 years.

This means that the longer the time frame, the lower the overall potency of methane in terms of its Global Warming Potential equivalent. (Or “GWPe” – simply a measure of the warming capacity of a particular gas, relative to the baseline warming potential of the most common greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide; which itself is very prevalent in the atmosphere but has a fairly weak warming affect per molecule, expressed as a GWP of “1.”)

Typically, methane is expressed in terms of a GWP over a term of 100 years, over which it has a value of about 23 or so.

That is, each unit of mass of methane, first as methane and then as breakdown products, including carbon dioxide, will have about 23 times the effect, in terms of total thermal radiation absorption and re radiation, as each unit of mass of carbon dioxide, over a 100 year period.

Over a shorter time period, which means that for a higher percentage of the total time any particular molecule of methane still exists as methane – where it’s vastly more effective at “trapping” heat than carbon dioxide – the GWP again is far higher.

But it’s not, as some articles may inadvertently lead you to believe, that methane is “23 times more effective at trapping heat.” (It actually a few hundred times more effective, but again, it doesn’t last very long).

It’s that over X period of time, a unit of methane will average out to have an effect that is about Y times as effective at trapping and re radiating thermal radiation energy, as the same unit mass of carbon dioxide.

But, just for example, over a century period a release of 10 gigatonnes of methane gas (a very large amount), would essentially have a similar effect, averaged out, of about or up to 230 or so gigatonnes of carbon dioxide over about a hundred years, and thereafter have around the same ongoing effect as carbon dioxide, since that is essentially what most of it will ultimately be. (A tonne is a metric ton, or about 2200 pounds. A gigatonne is one billion tonnes, or about 2,200,000,000,000 pounds.)

Notice also, though there’s little in the way of information that would tend to support or refute such an idea at his point, that if very large scale sea bottom warming were to occur over a short period of time, and thus massive amounts of methane released, the higher warming intensity of methane over a shorter term time scale would become more relevant – particularly if it was released in significant enough quantities to have a shorter term accelerating impact upon other climate driving conditions.

This same possibility also exists with respect to the vast northern permafrost; which when it melts will release some of its vast trapped carbon in the form of methane, and not just carbon dioxide, as well.

Enormous releases over, say, a 10 to 20 year period (or high enough sustained releases to keep the overall level much higher over a longer period) would make the relevance of methane’s higher GWP over that shorter period much more relevant, since the combined short term affect (or longer if suddenly much higher levels maintain through high sustained release), could quickly accelerate air temperature warming, and then further amplify ice melting rates. Over a 20 year period for instance, methane again has a much higher global warming potential equivalent (about 72 to 90.) than the 23 or so typically used for the gas, and based on a 100 year projection.

Thus an explosion into the air over say 20 years, of just a gigatonne of methane, would have up to the same short term affect of around 70 or more gigatonnes of carbon dioxide. 10 gigatonnes would have up to the effect of over 700 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide – near the total amount already in our atmosphere.

It’s not quite that simple, since the atmosphere is a balance, and some excess gas will be absorbed into the carbon cycle. But as methane and not carbon dioxide, and over a shorter time frame, this is less relevant – and huge influxes in particular in a short time also allow for less time and room for quick integration into the total global system, even as some of the methane starts to break down after several years; so a big spike in methane releases would have an extremely powerful and fairly rapid amplifying energy effect, on top of the level of permafrost melt or sea bottom floor melting that led to the release to begin with.

And it would be pretty wild, which we still don’t seem to be fully grasping.

_______

Remember, aside from what are in the short term uncontrollable geologic emissions created by an increasingly altering climate, if we take steps to reduce methane emissions, we can reduce atmospheric levels of it pretty quickly, since it lasts as methane for only a short period of time.

And, barring an acceleration in “natural” (ir climate change induced) net methane releases, because of its fairly short half life it takes a continuation of very high emission levels just to maintain current high levels.

But levels of the gas aren’t going down.

And in the earlier 2000s, methane levels, albeit very high, seemed to stabilize and even slightly decrease, and since – despite if anything a likely cessation in total net emission increases, or possibly a small decrease – have been slightly increasing.

Once again, take a look at the EPA graph from above. And the more geological time oriented chart on the left:

Now in the context of some of this additional information, notice again and almost identical in general pattern to an 800,000 year graph of atmospheric CO2 – that until recently – just about the start of the industrial revolution or thereabouts – atmospheric methane levels stayed relatively stable over long periods of time, varying between 450 to 700 ppb for most of the time covering almost the last one million years. And never rising above about 780 ppb. (And then essentially, from a geological perspective, as with carbon dioxide, they have shot straight up.)

With current methane levels at a little over 1800 ppb, a spike in a portion of the arctic atmosphere to over 2600 ppb (and now over 2800 ppb) is significant.

But it is what is happening more directly in the arctic system itself that is even more significant, and also fairly interesting. And, as with almost all aspects of the phenomenon known as climate change, here is where again the issue of a warming globe – not just a warming atmosphere, but far more relevantly, a warming globe – becomes very relevant. As does the issue of an ongoing yearly average decrease in arctic sea ice extent; which, on average, is leaving less and less ice in the late summer and early autumn months to cover up the otherwise dark, solar radiation absorbing arctic ocean relevant.

Robert Scribbler explains:

Imagine, for a moment, the darkened and newly liberated ocean surface waters of the Kara, Laptev, and East Siberian Seas of the early 21st Century Anthropocene Summer.

Where white, reflective ice existed before, now only dark blue heat-absorbing ocean water remains. During summer time, these newly ice-free waters absorb a far greater portion of the sun’s energy as it contacts the ocean surface. This higher heat absorption rate is enough to push local sea surface temperature anomalies into the range of 4-7 C above average…

Some of the excess heat penetrates deep into the water column — telegraphing abnormal warmth to as far as 50 meters below the surface. The extra heat is enough to contact near-shore and shallow water deposits of frozen methane on the sea-bed. These deposits — weakened during the long warmth of the Holocene — are now delivered a dose of heat they haven’t experienced in hundreds of thousands or perhaps millions of years. Some of these deposits weaken, releasing a portion of their methane stores into the surrounding oceans which, in turn, disgorges a fraction of this load into the atmosphere.

This, along with the melting ice both on land and on sea, in polar regions and in permafrost regions (which themselves hold nearly twice as much carbon as is currently found in the entire atmosphere – some of which, again, will also emit as methane as the permafrost melts) and the increasingly warming ocean – also again, at a startlingly fast rate – is one of the many important aspects of this complex, non linear, dynamic, and system shifting process of climate change that are largely being overlooked in the popular discussion and media, as the issue gets oversimplified by a near obsessive, and very misleading, focus on air temperatures.

Although we focus on air temperatures for a practical reason – we can relate directly to air temperatures, and we even, literally “feel” it – this only tells a small part, and often a very misleading part, of the relevant story.

The bigger story is one of great change, and it is being told not just in the atmospheric record that reflects our atmosphere’s now multi million year long term molecular heat energy re absorption property, but increasing, in the tell tale signs of a changing, if not slowly rumbling and even now occasionally erupting, earth.

Update: More information on methane, and why it’s future impact may be greatly underestimated, is found here.

[…] Major Methane Spiking in Response to Warming Arctic Waters is Starting to Skyrocket Area Methane&nbs… […]

LikeLike

[…] Sky Rocketing Arctic Methane Levels Help Tell Part of the Much Bigger Story of Major Change […]

LikeLike

[…] but, given the way earth’s long term climate system ultimately works, far, far from it; as methane is starting to erupt from warming ocean columns and the overlapping edges of land based polar ice sheets are melting from warmer waters, with at […]

LikeLike

[…] but, given the way earth’s long term climate system ultimately works, far, far from it; as methane is starting to erupt from warming ocean columns and the overlapping edges of land based polar ice sheets are melting from warmer waters, with at […]

LikeLike

[…] but, given the way earth’s long term climate system works, ultimately far from it; as methane is starting to erupt from warming ocean columns and the overlapping edges of land based polar ice sheets are melting from warmer waters, with at […]

LikeLike

[…] levels in the arctic have been spiking to unheard of high levels. What does this mean? Signs of what we would consider enormous changes brewing in the arctic, for […]

LikeLike

[…] levels in the arctic have been spiking to unheard of high levels. What does this mean? Signs of what we would consider enormous changes brewing in the arctic, for […]

LikeLike

[…] For the climate change “skeptic” who wants to stay a skeptic, this will not matter. But it is an important part of the issue to be covered, because the confusion over models has played an extremely large role in overall perception on climate change. And this fact that we can’t predict exactly what will happen, thus erroneously serves as a main basis for refuting the fact that atmospheric alteration is both significantly affecting climate, and more importantly creating a large risk range of potential affects. […]

LikeLike

[…] For the climate change “skeptic” who wants to stay a skeptic, this will not matter. But it is an important part of the issue to be covered, because the confusion over models has played an extremely large role in overall perception on climate change. And thus this fact that we can’t predict exactly what will happen, erroneously serves as a main basis for refuting the fact that atmospheric alteration is both significantly affecting climate, and more importantly creating a large risk range of potential affects. […]

LikeLike

[…] For the climate change “skeptic” who wants to stay a skeptic, this will not matter. But it is an important part of the issue to be covered, because the confusion over models has played an extremely large role in overall perception on climate change. And thus this fact that we can’t predict exactly what will happen, erroneously serves as a main basis for refuting the fact that atmospheric alteration is both significantly affecting climate, and more importantly creating a large risk range of potential affects. […]

LikeLike

[…] relation to the relevant issues we face, such an expression is pure semantics, and meaningless. (Much like, if not even more so, […]

LikeLike

[…] Thus, the goal should be to lower total long term ambient greenhous gas levels at this point. As Jason Box, one of the world’s leading glaciologists, and many others, strongly suggest. Unfortunately, right now we’re even still increasing them. And, again, as permafrost regions melt and release carbon, and even sea floor methane eruptions, already starting in a powerul way in the heavily warmed shallower waters of the arctic region, we may start to get a significant amount of amplifying help as the future unfolds – not in reducing levels, but in adding to them. […]

LikeLike

[…] into an astonishingly short geological time frame, the geophysical record, the risk ranges presented, or the intense, and increasing, record of geophysical signs of beginning […]

LikeLike

[…] into an astonishingly short geological time frame, the geophysical record, the risk ranges presented, or the intense, and increasing, record of geophysical signs of beginning […]

LikeLike

[…] The ultimate problem presented by climate change is also a matter of the ranges of risk of increasing radical future climatic shifting, in response to the ongoing, and cumulative effect of an already changed atmosphere and its accumulating impact upon the heat energy balance of the earth – and risk management. (A classic and in sufficiently covered example of just such potentially compounding, and even strong feedback threshold approaching, effect, is here.) […]

LikeLike

[…] lead to a relevant reduction over a few more decades and thus mitigate what is right now a rather profound risk range of major to radical, if unpredictable, long term climate […]

LikeLike

[…] An increase from 300 to 400 parts per million is an increase of 33%. A third is not even subtle in pure number terms, putting aside even the more important fact that pure number terms is not what’s relevant. Yet levels just in the industrial era have even risen more than a third, as have levels of other key greenhouse gases, with the next most important one rising far more. (Underestimated methane has more than doubled, for instance. And while it’s hard to assess levels going back millions of years, it, like carbon dioxide, essentially has suddenly shot straight up- and way up – from otherwise fairly measurable levels dating back trhough about 800,000 years or reliable ice core sampling. That’s very far from subtle as well, and part of the overall impact upon long term climate which the article references – a very key part.) […]

LikeLike

[…] be to us a reasonably long, but in geological terms very quick – time frame. (Here’s one such mechanism that gets far too little attention, as we over focus on air temperatures alone, which only tell the […]

LikeLike

[…] be to us a reasonably long, but in geological terms very quick – time frame (Here’s one such mechanism that gets far too little attention, as we over focus on air temperatures alone, which only tell the […]

LikeLike

[…] So of course climate likely has to change, possibly in (to us) geologically profound ways. And our sudden geologically relevant change to the atmosphere’s long term, and accumulating, recapture of energy presents an enormous risk range of what to us may seem “slow,” but would in fact be geologically very rapid and (again, to us), potentially severe lurches or changes that are probably still hard to fully comprehend or predict. […]

LikeLike

[…] that there isn’t a significant enough chance of it or even enough of a reasonable (let alone likely) chance of a major impact on long term climate to sensibly mitigate it; or at least stop adding to […]

LikeLike

[…] that there isn’t a significant enough chance of it or even enough of a reasonable (let alone likely) chance of a major impact on long term climate to sensibly mitigate it; or at least stop adding to […]

LikeLike

[…] (Possibly even as long as fifteen million in the case of carbon dioxide, and who knows in the more enigmatic, and often very underestimated case of […]

LikeLike

[…] (Possibly even as long as fifteen million in the case of carbon dioxide, and who knows in the more enigmatic, and often very underestimated case of methane.) And it’s invariably changing earth’s net energy balance – not […]

LikeLike

[…] Possibly even as long as fifteen million in the case of carbon dioxide; and who knows in the more enigmatic and often very underestimated case of methane, but almost assuredly well above – more than double – what the earth […]

LikeLike

[…] the case of the “lead” greenhouse gas carbon dioxide; and who knows in the more enigmatic and often very underestimated case of methane, but almost assuredly well above – more than double – what the earth […]

LikeLike

[…] gas carbon dioxide (but more likely at least several million or so); and who knows in the more enigmatic and often very underestimated case of methane, but methane has at least almost assuredly risen well above – in fact, more […]

LikeLike

[…] Climate Change, “Ske… on Sky Rocketing Arctic Methane L… […]

LikeLike